The city of Knossos was the principle population center of Minoan civilization, and the site of the largest Minoan Palace ever built (20,000 square meters, or 5 acres). Human beings have been living there since at least 6,000 BC.

The original palace, located about 5.5 km south of the shore of the Sea of Crete at Heraklion and next to the Krairatos River, was built around 1900 BC., atop the ruins of older settlements. Knossos was the largest Bronze Age settlement in Greece, and the oldest European city. During the so-called First Palace period, the city was estimated to be about 18,000 in population. At its peak, around 1700 BC and later, the city was thought to be home to some 100,000 people. It had extensive trade relations with other population centers in the Mediterranean, and controlled the affairs of the entire island of Crete.

Knossos in Mythology

Greek mythology claims that the Palace was designed by the architect and inventor Dedalos for king Minos with a floor plan so confusing and complex that no one who wandered into it could find his way out. King Minos then held Dedalos and his son, Ikaros, prisoners in a tower room, preventing them from leaving and revealing the floor plan to outsiders. That's when Dedalos devised wings of feathers and wax for himself and Ikaros, which allowed them to escape. Dedalos warned Ikaros not to get carried away with the thrills of flight and get too close to the sun. Like most young men, Ikaros, in his enthusiasm, failed to listen to his father's advice, and flew too close to the sun, which melted the wax on his wings and immediately put an end to his career as an aviator. Ever since, Ikaros has been used as an image of the person whose ambition carries him too high, too rapidly, causing his destruction.

The Labyrinth was, depending on the story source, either the complex layout of the Palace itself, or at another location, either near or under the Palace. (The idea that the Palace itself was the labyrinth is discredited today.) There dwelt the Minotaur, the horrible creature with the head of a bull and the body of a man.

The name is a combination of "Minos," and "tauros," that is, "The bull of Minos." The Minotaur is similar in appearance to the Phoenician god Baal-Molech, to whom child sacrifices were often dedicated by Phoenicians, other pagans in Palestine, and also by Jews during the first millennium BC who had drifted away from Mosaic Law and Jehovah worship.

King Minos, who otherwise was legendary for his wise policies as a ruler, forced the Athenians to send 7 young men and 7 young women, who were chosen by lots, to Crete, every 7th year. He did this because Minos's son, Androgeus, had been murdered by the Athenians. In history's first instance of germ warfare, Minos sent a plague to Athens in repayment for the murder of his son. In order to prevent the plague, Athens had to send its young men and women to Crete, where the Minotaur would devour them.

Then Theseus, the son of the Athenian king Aegeus (for whom the Aegean Sea is named), volunteered to go to Crete and kill the Minotaur. This he did with the help of Ariadne, daughter of Minos, who had fallen in love with the young hero and provided him with a ball of thread which he unwound as he navigated the labyrinth, which allowed him to find his way back out after he had dispatched the Minotaur.

By the way, the tale of the young men and women drawn by lots and sent to their deaths in Crete was the germ of the story in the recent Hunger Games series of bestsellers and movies.

Origins, Discovery, Excavations

The name "Knossos" been handed down from ancient Greek sources. The city's location comes from tradition, which was confirmed by the presence of Roman coins spread about just north of the site where there was a Roman settlement called Colonia Julia Nobilis Cnossus. These coins had the word "Knosion" or "Knos" on the obverse ("heads"), and images of a Minotaur or Labyrinth on the reverse. The Minoan-era ruins were under an unexcavated mound on an 85 meter-high promontory known as Kephala Hill.

There are a couple of versions of the first excavations of Kephala Hill. We'll stick with the one most likely to be true, namely the discovery in 1877 of the site, or, rather, confirmation of the tradition of the location of Knossos, by a Cretan merchant/antiquarian named, appropriately, Minos. His last name was Kalokarinos ("Summer"). He started excavating in 1878, uncovering west wing storage magazines and part of the west facade. His 12 trial trenches covering a large sector of the site uncovered large storage containers known as pithoi, some with foodstuff in them, and stone walls into which the double axe known as the "labrys" had been chiseled.

Etymologists think the word "labyrinth" comes from labrys. The double-bitted ax is one of the oldest symbol in Greek civilization and has a relation to female divinities. A translated tablet from Knossos refers to the "mistress of the labyrinth-" the goddess of the double ax- who superintended spiritual life at the Palace. The ax itself was used by Minoan priestesses to kill sacrificial animals. Priests at Delphi in Classical Greece were known as Labryades, or men of the double ax. This symbol had been used in Asia Minor as early as 7500 BC.

The work of Kalokarinos took place during the time Crete was busy freeing herself from the Ottomans. During this time of conflict his house in Heraklion was burned, along with some finds from the site, and his field notes. After several years of unrest, things settled down enough for excavations to continue in 1900 under the supervision of Arthur Evans, an English archeologist. He and Heinrich Schliemann, discoverer of Troy, were considered the pre-eminent Bronze Age Aegean archeologists of the age. They knew each other, and Evans had come to Schliemann's sites, but Schliemann died before getting a chance to visit Knossos.

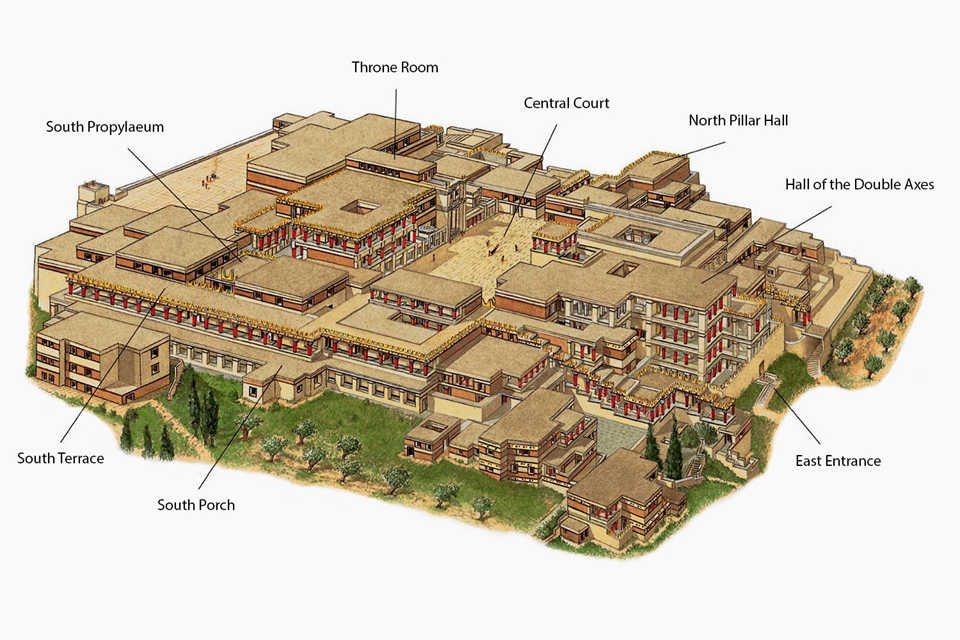

Evans had used what he called "educated guesswork" to restore parts of the Palace, including the Grand Staircase, some columns, the Throne Room, and the Hall of the Double Axes. Evans had purchased the entire site from the Turks, so he felt free to restore some parts of it. The restorations have proved controversial, with some people thinking them tantamount to desecration, and others praising the work as helping to give the modern visitor a clearer idea of what the palace looked like.

Evans, who mostly self-financed the excavations, found himself broke by 1906. He then used an ongoing allowance from his father to build a house in Heraklion. In 1907, Minos Kalokarinos sued Evans, claiming he had removed antiquities from the site, had excavated without permission, and had taken possession of a field on the site without paying Kalokarinos for it. The charges were true on their merits, but the death of Kalokarinos resulted in their dismissal.

In 1908 Evans's father died, leaving Evans with a considerable fortune. But the work at Knossos was largely done. He published his findings in a document praised for its accuracy. Over the years, as Evans directed from Britain more restoration and some excavation work, the costs of maintaining the site at Knossos became prohibitive, and he ended up donating it to the British School at Athens, who would take over the site and use it as a place for training young archeologists. A lot of restoration/reconstitution work took place between 1922-1930.

The Palace

The first Palace was built in about 1900 BC on the ruins of a Neolithic settlement. It was destroyed around 1700 BC, and a new Palace was built. Although Knossos as a city-state continued to exist into the Byzantine era, the Palace was abandoned sometime between 1380-1100 BC, when much of the Minoan civilization collapsed following the Minoan Eruption of the volcano on Santorini, to the north.

Following the building of the Second Palace, the Minoans reached their peak during the next 250 years. The Palace, and the city-state, would suffer from devastating earthquakes at regular intervals.

As you walk up the ramp leading up to the west entrance, there are 3 large, round pits called kouloures, which, at their bottoms, give you a view of some pre-palatial ruins. The Palace was jammed full of workshops, storage magazines, meeting rooms, apartments, and other spaces related to the running of an island empire. It had beautiful, elaborate wall paintings, some of which have survived and can be found in the Heraklion Archeological Museum.

There was a Throne Room with a gypsum throne, a central courtyard, a theatre, and royal chambers. It was a place of religious ceremony and ritual, and a place of governmental and civic functions. North of the Throne Room are the Minoan Frescoes, in a room Evans restored. It has copies of the frescoes "Spectators by the Shrine" "The Argonaut," the "Blue Monkey," and the famous "Bull Leapers." The originals can be found in the archeological museum in Heraklion.

The Grand Staircase leads from the Throne Room up to the Royal Apartments, which were built into the hillside. The Staircase is highly regarded architecturally for its use of a light well. Evans believed the West Side of the Palace was 5 stories high, while the East Side was 3 stories high.

The climate, with its heavy winter rains, was hard on the building materials used, which included wood, mud bricks, and alabaster (made of relatively porous gypsum and calcium). This led to the invention of one of the world's first drainage systems. The Palace has some remarkably advanced architectural features, such as painted plaster walls, light wells, "polythura" (rows of doors set into a wall which were opened to create a larger space or allow more light), and wooden beams to reinforce its masonry.

The Palace is built around the large Central Court, which was used for mass public meetings. There was a Western Court as well, used as an approach to the ceremonial area.

The West Wing

The West Wing was used for administrative purposes and religious activities. Here was found the Tripartite Shrine, which was the main sanctuary. South of the Throne Room, this is where the famous "Snake Goddesses" were found; figurines of a woman holding a snake in each hand and now on display at the Heraklion Archeological Museum. The Snake Goddess was a supreme deity. She may have been the precursor to the Greek goddess Eurynome, who danced with a serpent over the primordial sea in an act of creation.

In addition to the Tripartite Shrine, the West Wing contained Sacred Repositories (for which the Tripartite Shrine served as a facade), and "Pillar Crypts," which was a term Arthur Evans invented to describe small, subterranean windowless rooms with a square central pillar with basins to either side of it connected by shallow channels. The pillars have the double ax engraved on them. Pillar worship involved the idea of the deity, usually female, living in the pillar.

Behind the ceremonial rooms were the West Magazines - long, narrow rooms used for storage. They were full of pithoi- large clay containers holding grain, other agricultural products, oil and wine.

The South Wing

The South Wing has the Corridor of the Procession, which had a "Fresco of the Procession," featuring cupbearers and harpists, and the so-called "Prince of the Lilies," a strolling man wearing a necklace and a crown of lilies. Frescos were executed quickly on wet plaster using dyes extracted from plants. The colors would bleed deeply into the plaster, and are just as bright 3,500 years later as they were when originally painted. In the midst of the Corridor is the South Propylon, named by Evans after the the monumental gateway of the Acropolis in Athens. Its inside walls were covered with gypsum, and several layers of plaster.

The East Wing of the Palace contained the Minoan Workshops, incuding lapidary (jewelry) and potters' workshops. It is believed that east of the Palace was where the bull-leaping arena was. King Minos Apartments is also known as the Hall of the Double Axes, because of the double axe carvings on the walls.

To the north were the Theatre and Customs House. The Customs House has a Lustral Basin, thought to be used for ceremonial cleansing and other religious purposes. Because of its position as the first building one comes to from the harbor, Evans believed it to be a Customs House. The Theatre is north of the Palace. It seated 400 people, who probably watched religious-themed spectacles. The Royal Road leads north to the Little Palace, thought to be the villa of a wealthy citizen or a member of the royal family in the wealthier part of the city. Architecturally similar to the Royal Palace, its main difference is that its dimensions are much smaller.

The Royal Tomb of King Minos is outside the Palace proper and is where Evans last excavated, in 1931. He believed King Minos was buried here. It dates from around 1400 BC, when the Mycenaeans were taking over the island, and is where Evans believes feasts dedicated to the dead king were held. Whether this is Minos's burial spot has never been proved or disproved.